Daniel Milnor--- 12 May 2016

By Lorenzo Princi

What do you two do?

What do I do? As little as possible [laughs], no I do-- I work as a photographer at large for Blurb and then in addition to that I try to do a lot of projects on my own so I spent many years as a photographer and I still kind of have that in my blood. So on the side I’m trying to produce photography projects, art projects, collaborations and books.

Your work involves a fair bit of travel and you seem to be someone who likes to get out and be where the action is with a no fear approach? Why do you feel it’s important to get out of the your zone?

Well you know I’m fortunate because the Blurb job allows me to travel a fair amount, I’m at the end of about a five week road trip that started in the Netherlands, went to London and ended up here in Sydney. So, it’s a wonderful thing to get out. From the work perspective, there’s nothing better than standing in front of people who want to use what you are making and it’s a great way to get feedback. Last night I was with a group of Sydney based photographers, a collective group and we looked at work and looked at books and it was fantastic. I felt like that’s really the reason to be in the field, is to be able to do things like that.

And for me on a personal level and travelling and making work it’s just about story. I find, any kind of story that I find interesting-- people, place, location, events, I want to go over and over and over to be there because, unlike, let’s say a journalist who is working with just the written word, you can sort of do that from anywhere, but with photography, you have to be right on the front, that’s the tip of the spear basically. Which is both I guess, a blessing and a curse at times. You can go, “what the heck am I doing here” and at other times, “this is the most amazing day of my life,” so, that’s what’s fantastic about photography.

"It’s a wonderful thing to get out."

Your early career was as a commercial photojournalist can you talk a little bit about that?

[Laughs]. It’s funny because I was freelance for many years. I had my own business but I was freelance and my father used to love to say, “mostly free, little lance” [laughs]. So it was very difficult to get work, it was always a struggle to do that but I started my career as a newspaper photojournalist because I had no idea what I was doing and that was an amazing training ground from day one, they just threw me to the wolves and within a very short period of time you're either going to be able to do it or you're not and then I-- but what I wanted to be was a magazine photographer because it seemed far more exotic and at the time there was this really interesting path where you started at a newspaper and on the site you started freelancing for magazines and then you eventually made the jump. You quit the paper and went to magazines.

Most of that is no longer in existence but that was the path that I took and-- but something weird happened and I-- four of five years into this sort of career I guess you could call it, though that’s loosely using that term. I realised that the only work I was concerned with making was my own and that I wasn’t entirely sure that I could work and make my own work. People were not interested in it, they were only interested in a very specific type of photography that really didn't interest me, so I ended up quitting photography and that’s what really led me to understanding who I was with a camera and I still have to remind myself from time to time because it’s easy to get sucked back into the sort of mainstream.

"They just threw me to the wolves and within a very short period of time you're either going to be able to do it or you're not."

Why move into a riskier space with Smogranch and now Shifter.Media? Chasing artists instead of the mainstream story?

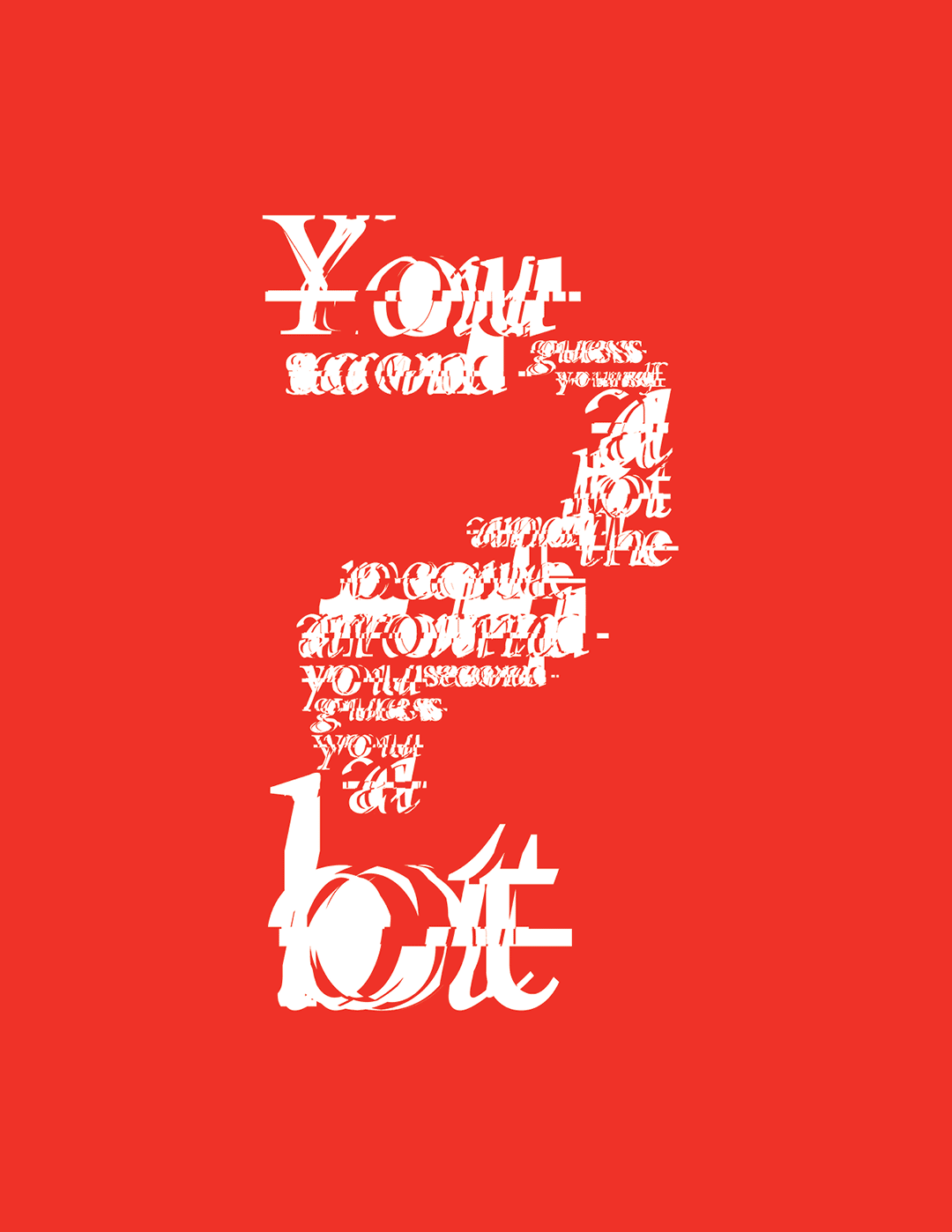

You know what drove it was realising-- well first of all there’s a couple of photographers out there that I look at and hold in very high regard and some of them are long since-- since past and others are working and operating today and I think anybody who gets into the documentary photography world-- you look at people like Gene Smith, Sebastião Salgado and then, speaking about Australia, you look at a guy named Trent Parke and those three people to me are sort of the pinnacle of who I-- I would strive to be as a photographer and they work in a very specific way and that way has almost nothing to do with actually being a professional photographer. They’re almost in a way, beyond it. Gene Smith, allegedly and I don’t know this for sure but the stories I’ve heard is that he died with like fifteen bucks and he was the most possessed person on Earth. Everyone had trouble working with him. He did a story on Pittsburgh and they told him to deliver like ten images and he delivered ten thousand and I think if you look at Smith and Salgado and Trent Parke, these guys sort of operate in that-- and that’s-- you can’t do that inside the industry because there’s no time and budget you just have to find a way to do it on your own.

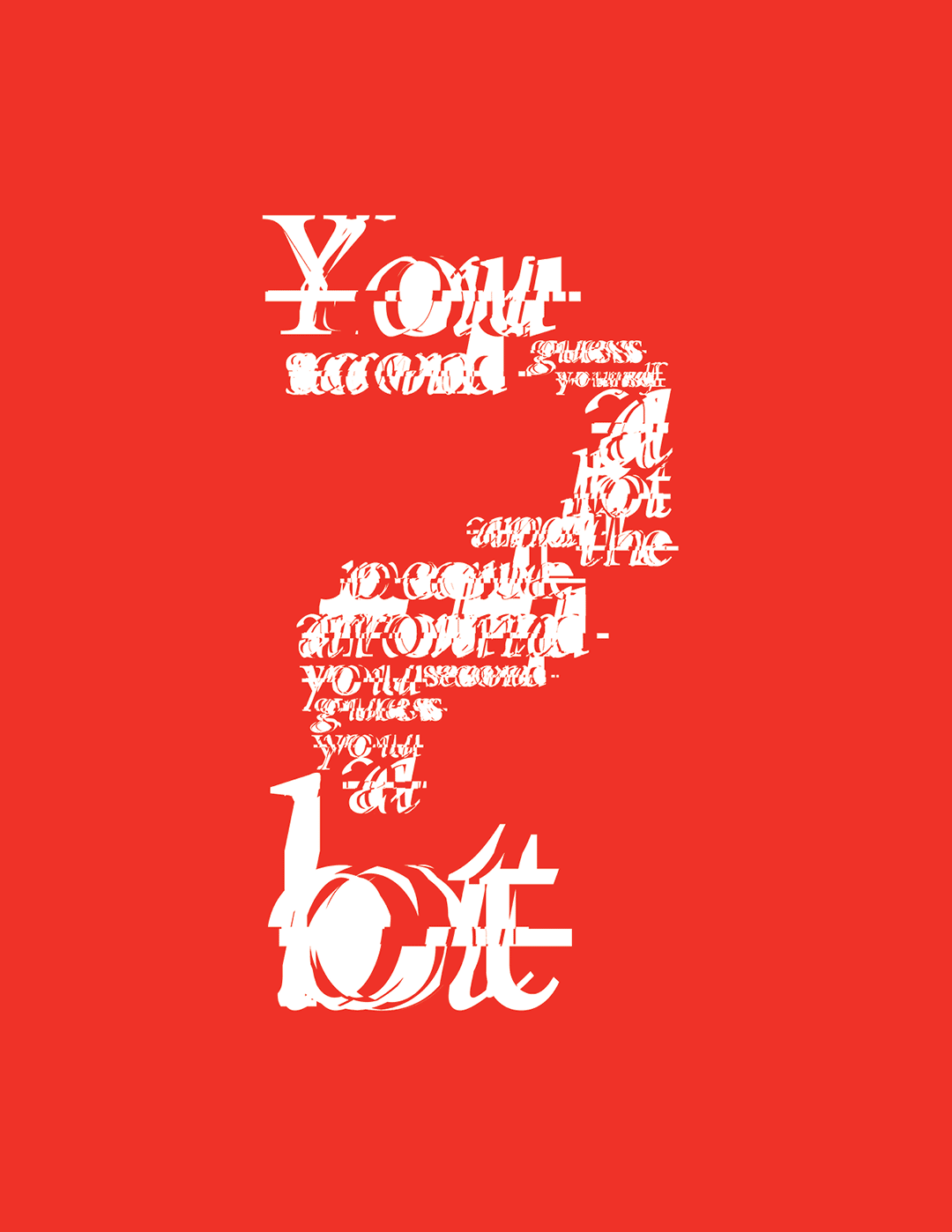

And so it is risky and it’s, you second guess yourself a lot a lot and the people around you second guess you and your colleagues second guess you and there’s-- you have to be driven to do it otherwise it just won’t happen.

"You second guess you and your colleagues second guess you."

You're passionate about photography and it’s an industry that has been through a lot of change in our lifetime. Everyone has a camera in their pocket nowadays and everyone is sharing their photos. What are your thoughts on that?

Well, I have to be very delicate about this because I don’t want to infuriate people but I think there are, like most things in life-- there’s an upside and a down side. I think for everyday people that are not professional photographers it’s been a wonderful thing. I think, when digital arrived in the world, the photography industry was stagnant, it was actually getting smaller and digital arrived and injected like this new life into photography, not just for professionals but for the consumer market and for really-- for the first time since the Kodak Brownie camera people were jazzed to make work and to-- now we’ve gone a hundred times further than-- where-- than anyone expected to be.

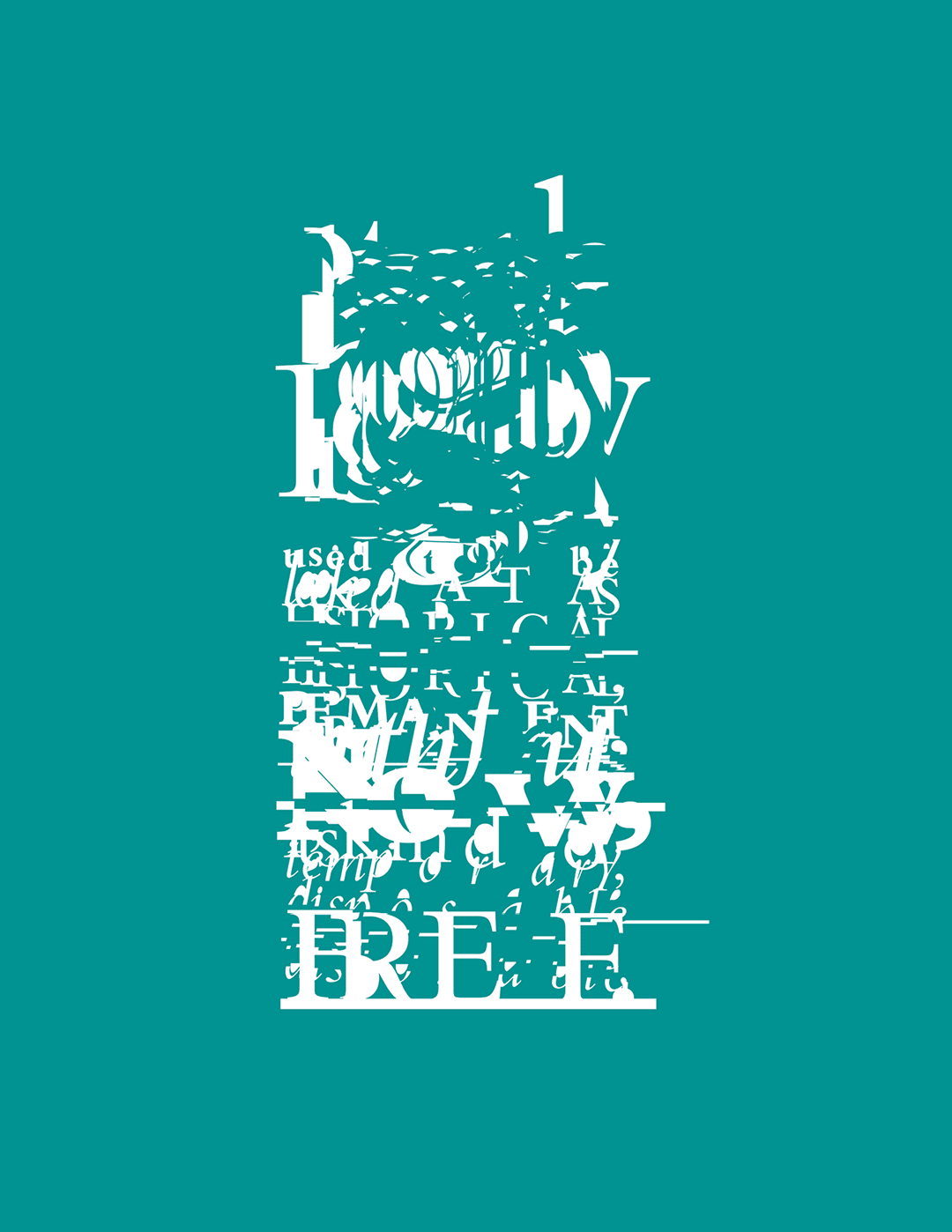

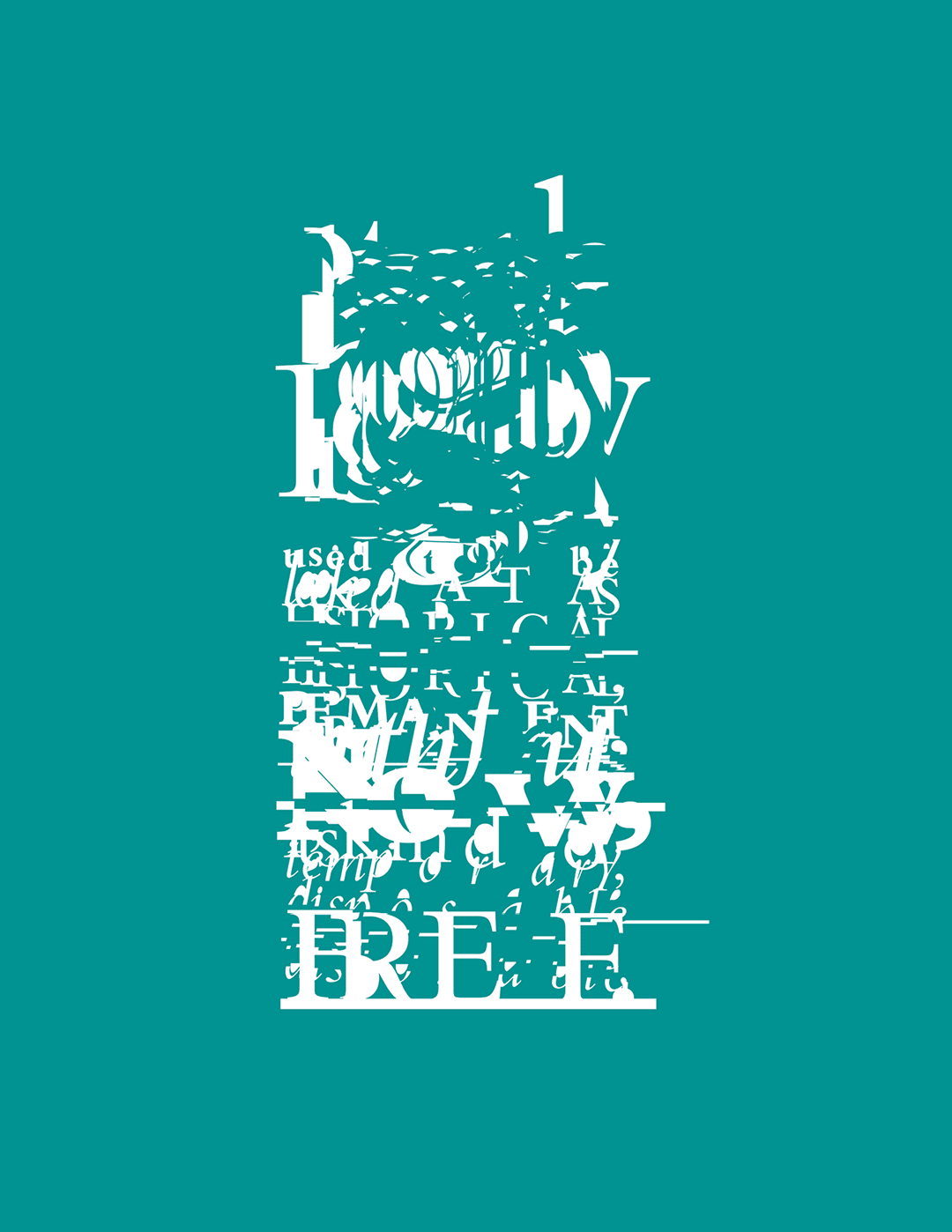

For the professional it’s been a slippery slope, it’s been-- there-- in some weird way it’s really undermined a lot of the relevance of photography, you know, photography used to be looked at as historical, permanent, truthful. Now, it’s kind of temporary, disposable, free and so if you’re working as a photographer-- an artist in photography, it’s a battle to get people to respect what it is that you’re doing and also to pay for it-- pay legitimate prices for it. So what you’ve got is a massive number of people who’ve thrown their hat in the ring and said, “oh, I have a camera and a website, I guess I’m a photographer too.” and for me-- and that’s totally fine, people are obviously free to do whatever they want but for me, saying that, "I am a photographer" is sacred ground and I actually don’t call myself a photographer any more because I don’t make my living from shooting pictures any more. I make my living working from Blurb and the photography I do is on the side. However I think the work that I’m doing now is as good or better as anything I’ve ever done I just don’t look at it as a revenue source because it’s more fun for me to operate independently without having to answer to anyone else.

"Photography used to be looked at as historical, permanent, truthful. Now, it’s kind of temporary, disposable, free."

Photographers can be controversial figures, invisible at times (especially when it comes to credit) or the headline in others. We've seen paparazzi attacked by celebrities or photographers called out as to why they didn’t help someone in distress instead of taking their photo. What is the role of the photographer?

Well the role depends on the genre, so if you’re an art photographer or a fashion photographer you play-- you play your part in the movie of photographic life where you’re a fashion guy. For me in particular being a documentary photography, that is a perpetual grey area. So, there are situations where and it is-- it is case by case, second by second within those stories where you see things-- anyone who is a documentary person or a photojournalist is going to be put in situations where you have an ethical and moral decision to make as to how you behave. Those lines have been clouded over the last ten, fifteen years. I mean, I live near Los Angeles and I have seen paparazzi do things that most people would not believe they do and I’ve seen them do it to each other and it’s really horrifying to see it but the reality is those images are the most in demand photographs in the world. They’re also the most sought after and expensive work in the world so… I would never, ever, ever do what the paparazzi do but I’m equally fascinated by them and I would totally do a story on paparazzi if they wouldn’t kick my arse which is what would happen! They don’t want to be photographed.

But I’ve never-- I don’t remember being in a situation where I thought, “I have to put my cameras down and help someone” because I’m not really a front line kind of photographer and the few situations that I’ve been in where it’s been dangerous I’m basically-- they’re-- the only thing that kicked in with me was, “I have to protect myself and get out of here.” It wasn’t, you know, any situation where it’s like, life and death on the line and I chose to make photographs.

"I ended up quitting photography and that’s what really led me to understanding who I was with a camera."

You have done some teaching. How do you find the experience of sharing you're knowledge and experience with those wanting to learn?

You know, that’s a really good question and I have gone through-- I guess you could say full circle on the teaching thing. When I-- when I got into photography I was never asked to teach and then I got into a period of photography where I was asked to teach all the time and I’ve taught in The States and I’ve taught in Latin America and and I taught in other places around the world and then I sort of came out of the other side and a part of that-- this might sound bad but a part of it was that when the digital age arrived, the meaning of photography changed and subsequently the students that I was teaching also changed. And I realised my ideals of what photography and what I sort of thought was good photography didn’t necessarily coincide with the masses of people who were wanting to learn photography. And I’m not a huge fan of sitting in front of a computer all day long and I realised that I was probably going to cut back on my teachings.

So, I still get asked to teach and there are some certain people that I would teach with-- I live in Sante Fe, New Mexico part of the time and there’s a-- Sante Fe Photo Workshops is based there and the director is a really wonderful guy and I would always take the opportunity to teach there if I could and then I work with another guy who is based in Seattle but he lives in Peru-- guy named Adam Weintraub and I teach with him-- typically teach once a year in Peru, although I’ve missed the last couple of years because Blurb’s kept me a little too busy. But if I was to teach again it would be a very atypical class which are really hard to fill. Like, I don’t want people to sit in front of computers and I want people that will take chances and not be afraid to go somewhere and come back without an entire portfolio of sort of expected images. I want people that are willing to take risks and go, “look I might not have come back with anything but I came back with an idea of where I might be as an artist somewhere down the road” that’s more important to me.

"I might not have come back with anything but I came back with an idea of where I might be as an artist somewhere down the road."

You connect with a lot of people and collaboration is a big part of your book making projects. Being very experienced and established yourself? What drives you to seek collaborative projects?

That’s another good question. The drive to collaboration came from Blurb taking up all of my time! And the Blurb job is the best job I’ve ever had by far but it’s not conducive to doing long term projects, I just do not have the time, so, in the past I would spend years working on a project and put it together and since about 2010 the timeframes that I’ve had has gotten shorter and shorter so I-- it was born out of frustration of not having any time and then also the frustration forced me to look at life in a different way and say, “okay, if I don’t have two years to work on a project, what can I do in two days by myself but then working with someone else, maybe they can help me turn it into something that’s better?”

So, I started doing collaborations with other photographers and designers, I-- in fact Chloe Ferris who is a local designer here (in Sydney) is someone that I met a few years ago and just immediately said, “Wow! This is someone that’s so far beyond my abilities that I would love to do something with her.” She’s been open to doing partnerships and now it’s-- it’s like the Pandora’s Box is open. That’s all I can think about is collaborating with other people and the last couple of days I’ve been doing a book sort of in real-time with Garry Trinh who’s a local photographer and Garry is a real quirky guy who’s very different than I am and just sitting and watching him work has been an education for me. How he sees photographs and he and I literally walked this exact same spot that we are (Watson’s Bay) and he sees things that I just do not see and it’s fascinating, he’s made me look at Sydney in a very different way.

So, I’m always-- the key is collaborating with people who are better than you [laughs]. Ultimately it makes people go, “Wow! You’re works really good!” and I’m like, “Not really” but what I’m really good at is connecting the people and I do the first little taste of the collaboration and then I let them go...

"It was born out of frustration of not having any time and then also the frustration forced me to look at life in a different way."

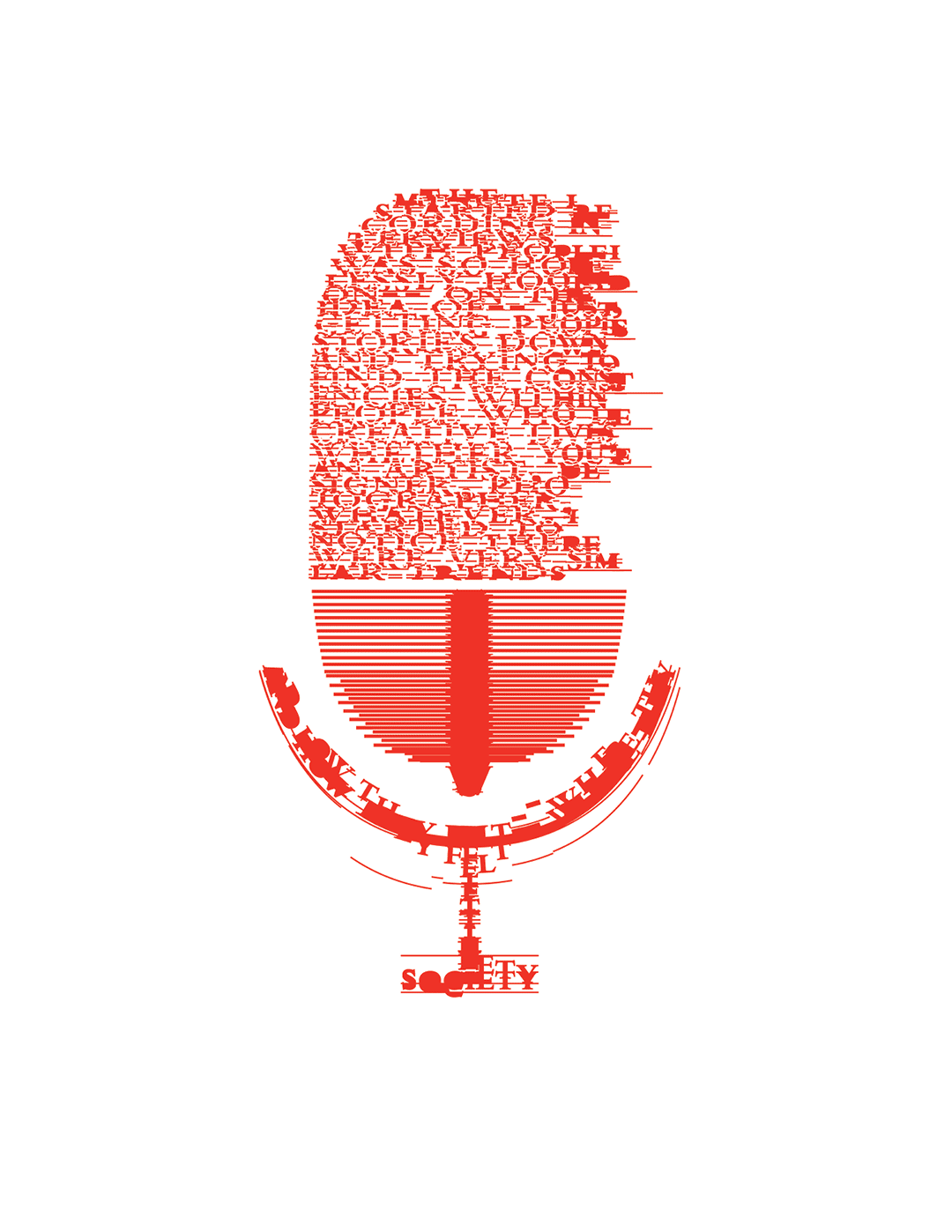

Your Shifter series is a unique story telling narrative. It’s as digital as they come but almost feels like listening to an old radio broadcast. It is very popular and you’ve interviewed some great artists. Why do you feel it’s important to use your own reach to share the stories of others?

Well, it started somewhat by accident. We had someone who was working at Blurb that called me one day and said, “hey, how do you feel about photographing people who use Blurb, who live artistic lives” and I said, “well, I’m already-- I already do that for myself on the side” and they said, “well, you know… let’s do a campaign.” So, I did three shoots in california and the first three shoots I did, I had amazing access and a lot of time and subsequently I came back with a pretty good body of work from each of these three people and the person at Blurb looked at it and said, “ah, oh, these are way better than we thought we can’t just willy nilly this out. We have to do a whole campaign around it.”

And there’s an upside to that and a downside when you hear that and the downside is the man power you probably don’t have to make a full campaign so the Shifter site came about because I needed a home for that work and what happened was, immediately-- because I studied journalism and photojournalism, I hadn’t done it in a long time and the minute I started recording interviews with people I was so hopelessly hooked on-- on the idea of-- just getting people’s stories down and trying to find the consistencies within people who live creative lives, whether you’re an artist, designer, photographer, whatever. I started to notice there were very similar trends and how people looked at the world and how they felt-- where they fit in society and all these different aspects. And now that’s all I think about, I’m doing another interview tomorrow. I’ve done four so far here in Sydney, this will be my fifth one and I-- if there was a way to do this and actually make money I would be trying to investigate that right now because it’s a lot of fun!

"I started to notice there were very similar trends and how people looked at the world and how they felt-- where they fit in society."

I guess we can say you come from the tradition media world however have not been shy to adopt new technologies? We’re in a transitional period now? What are your thoughts on these disruptive times?

Yeah I mean I think disruptive time-- I think actually we’re past the transition point but the-- the wave has crested and it’s rolling back and what you have in The States anyway is you have a lot of students-- photo students who want to learn analog because they grew up with digital and it’s nothing new to them and they’re very skilled with it and they want to see sort of where we came from. To me it doesn’t matter who you-- what you use, how you operate, that’s sort of inconsequential to me. The thing that’s important to me with, like, students that I would love to see is that I think now there’s maybe, there’s a little bit of a reluctance to sort of look around and outside of your own bubble and I think like-- when I’ll teach workshops and I’ll-- or I’ll go to an art school and meet the students and I’ll say, “who is you're favourite photographer?” And sometimes they can’t name a single other photographer and I think as a-- anytime you enter the creative field you sort of have to know who came before you, what they did and then what it does is it helps you figure out where you fit in the greater creative world and then you can saw, “oh, well so and so did this and I’m not going to copy them but I’m going to sort of try and tribute and reference them in the work that I’m doing, I’m going to build on what they already did.” But to do that you have to know who they were.

So, I think we are-- we will from this point forward, we will perpetually live in a disruptive state. I think our culture-- society in general, not even just photography and creatives. I think we’re disruptive and I also feel a little sad for the current generation because they were never given the opportunity of the foundation, let’s say, that I had. Of having a clear path to follow; newspaper, to part time freelance, to full time freelance, to magazine, to commercial, to advertising. That path was there and now it is gone. So the young creatives of today, they’ve got to blaze their own trail and that’s a really tricky, tricky thing to do.

Lorenzo: Hope their blog or their Instagram picks up…

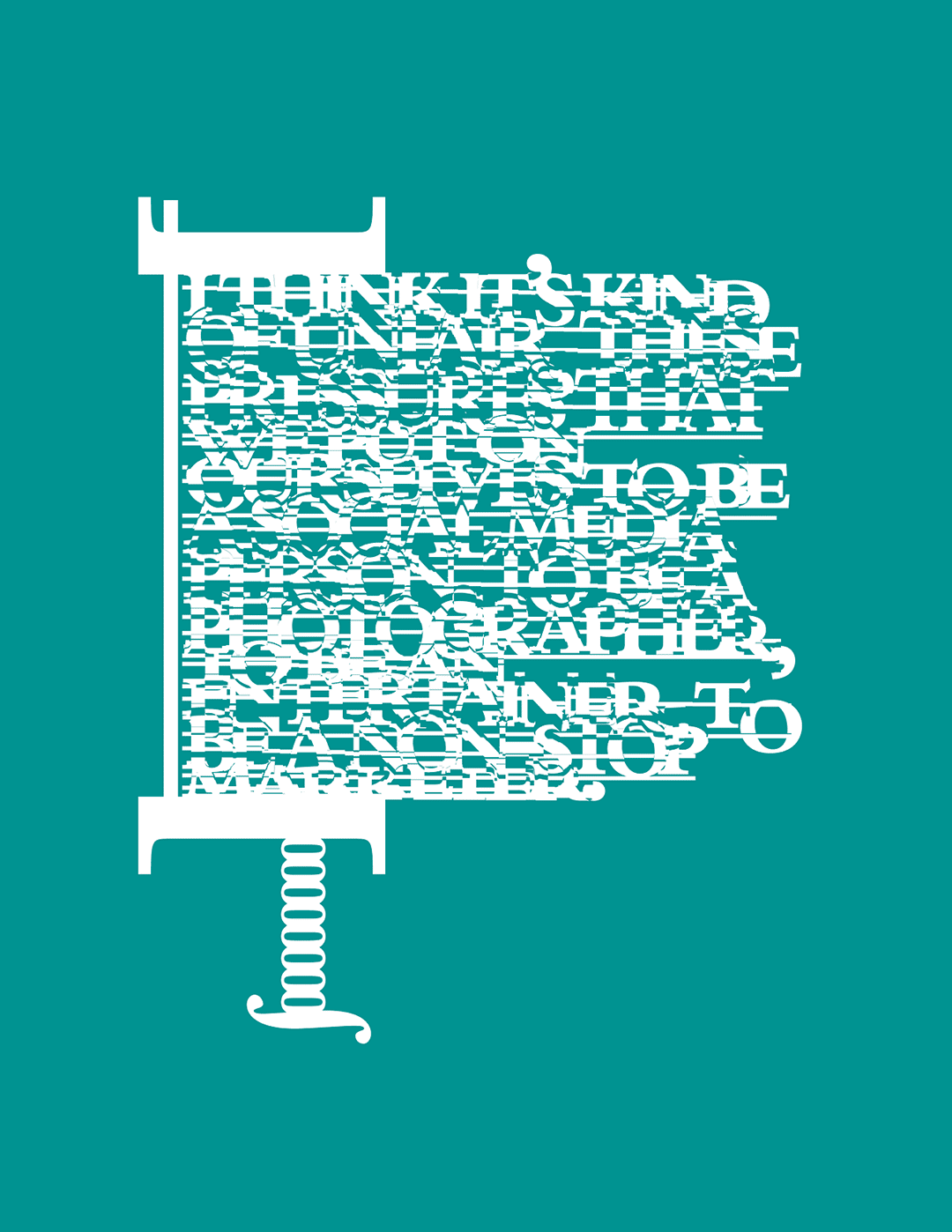

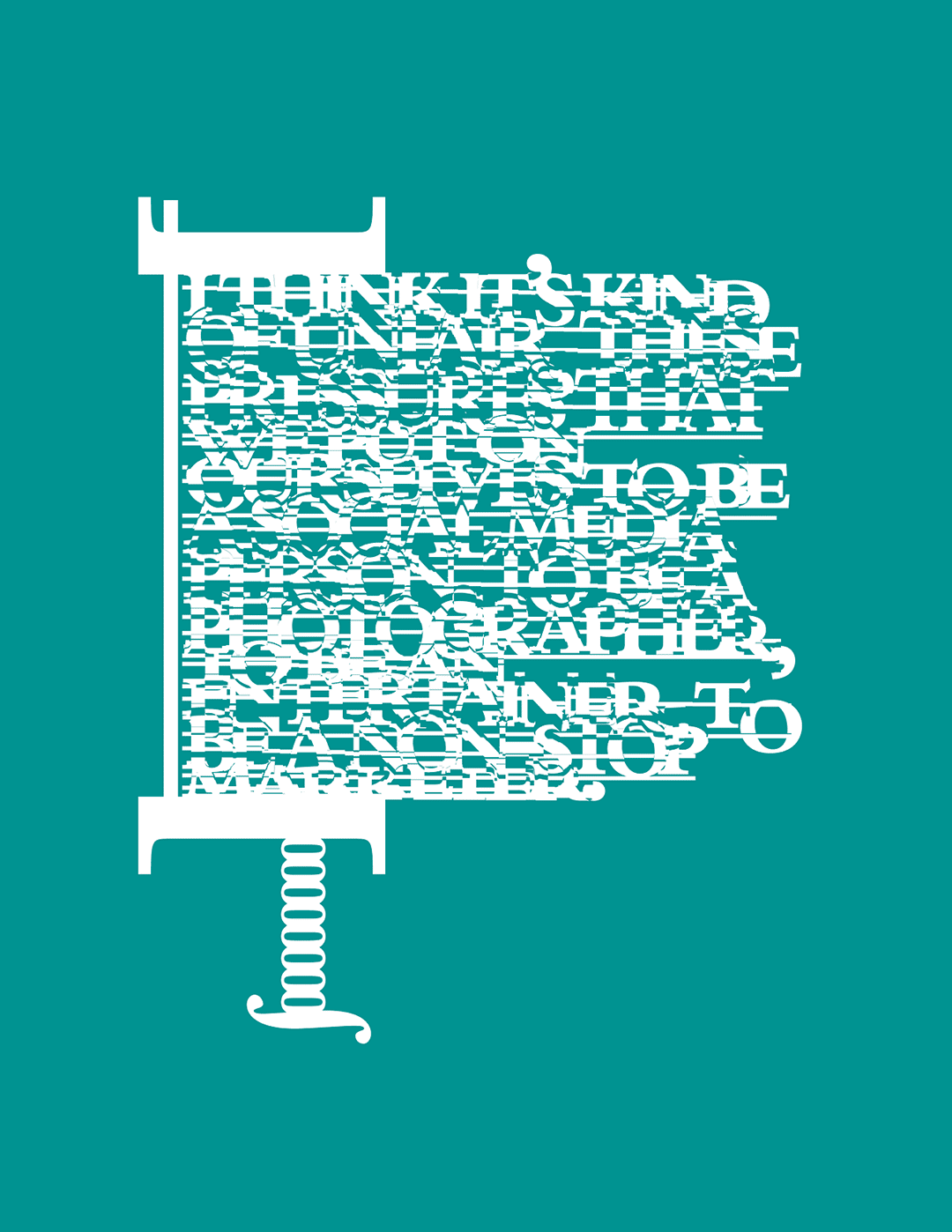

Daniel: And the thing is, the blog to me is a really interesting tool and the blog sort of was really powerful early on, then it sort of fell out of favour and now it’s coming back because the blog is a conversation. Social media is like a sound bite so the problem is that your Instagram account today is wonderful and you have all these followers but Instagram eventually will go away, just like every other platform we have and then you have to migrate to whatever is new and the thing to me is and I thought about this the other day. If you're-- let’s say that you’re a photographer and you and I are out here today and we’re working and we’re trying to document this exact cliff top or whatever. If I’m making pictures and I’m doing social media at the same time, it is an impossibility for me to do two things at once and expect to do either to the best of my ability because to really do either one of those it has to be a hundred-- a hundred and ten percent. Otherwise you’re going to get B-Roll stuff, it’s never going to be A-Roll so I think it’s kind of unfair, these pressures that we put on ourselves to be a social media person, to be a photographer, to be an entertainer, to be a non-stop marketer. It’s like, "make work" and especially for anyone in the first ten years of their career, forget about everything else and go spend every waking moment making the best possible work you can make because that will end up as a career. Social media to me will give you a couple of good years but that’s not a career.

"I think it’s kind of unfair, these pressures that we put on ourselves to be a social media person, to be a photographer, to be an entertainer, to be a non-stop marketer."

What's Next for Daniel?

What’s next? Well, it’s interesting, I go back to California, I’ve got a couple more domestic trips in the US-- San Francisco and then Virginia for a week for Look3 photo festival but last night I watched this film about Trent Parke-- I kind of have a man crush on Trent Parke [laughs], I’ll be honest and I was like five, ten minutes in and I had to stop it because it was just too much. It was too-- making me crazy in a good way and I have to start a new project and a real project. Meaning, going back to what I did prior to Blurb. I’ve got to do something, because it’s driving me crazy and I can’t wait any longer, you know, I’m forty seven, if I don’t go it now, I’m never going to do it. That’s what’s next.