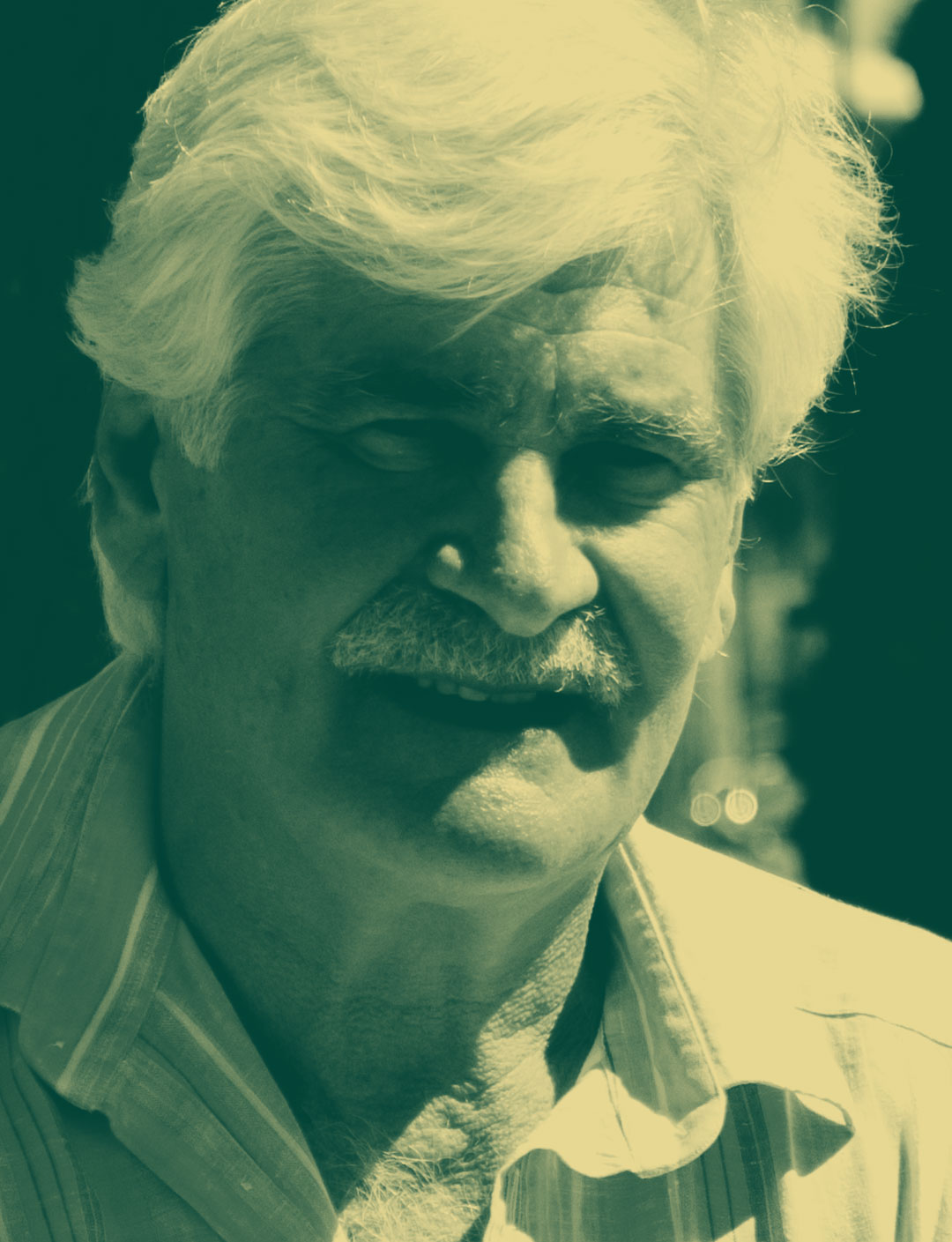

Bryan Forby--- 29 December 2015

By Lorenzo Princi

What do you do?

What do I do? I help people in areas that they have common interests. Fundamentally what my job is-- the basis of it is that we have groups of people and we have to assist them to manage their collective responsibilities which is a pretty strange thing for a lot of people. Because they’re always switched on to looking after their own personal interests or that of their family; the people close to them but people don’t get much practice at assisting each other to do things together. So getting collective decisions-- getting decisions by a whole group of people that is a collective decision-- there’s one decision but there’s a lot of people with varying ideas. That’s the trick, that’s the trick to what we do.

"People don’t get much practice at assisting each other to do things together."

You left a country town and went to University in Adelaide. How was that shift in lifestyle?

It was mind blowing! Because as prepared as I thought I might have been, it was a shock. It was probably the single biggest cultural shock that I’d experienced in my lifetime. Been to a lot of places and done a lot of things. Been to really weird places in weird circumstances but I’ve never been blown away like I was when I was a seventeen year old who left the country, came to the city, and studied at university. Yes that blew me away.

I wanted it all, I wanted it badly. I looked forward to leaving home, to moving into the big smoke and doing things at a different level, but it took me a while to get used to the idea.

"I’ve never been blown away like I was when I was a seventeen year old who left the country, came to the city, and studied at university."

How has travel helped define your outlook to work and life?

Yeah, I wanted-- I was looking for a challenge, looking for things to change my attitude really. I was out there, nudging at the fringes. I went basically around the world at the age of twenty seven. Spent a whole year away and went all up through Asia, across the Soviet-Union at that time, which was a rare thing. Stayed in Europe as a base, went to the Middle-East and worked on a kibbutz in Israel in tight times. We were near the Syrian border and at that stage that was a hot spot and I went to America as well and travelled all around America, literally bought a Chevy Camaro for five hundred bucks and drove it from New York to New Orleans, across to Los Angeles and California and back across the top and all the way back to New York City. So I did six thousand miles in that Chevy Camaro. Bought it for five hundred bucks and sold it for four hundred and fifty bucks at the end. So it cost me fifty bucks to travel America [laughs].

But, always looking for things that would blow my mind and I only found it in one place. In all of that travel, I found it in one place only and that was in Jerusalem, in the Holy City.

"I was looking for a challenge, looking for things to change my attitude."

You were a teacher before entering the corporate world. Why the switch?

I was heavily involved in sport from a very young age. That was my primary motive in moving to the city; to play sport at the top level. Just so happened that I got talked into undertaking university education at the same time, and that was fortunate because it’s the education rather than the sport that’s paid most dividends for me, but at that time I didn’t know it.

So, I did-- had-- I did the tertiary education and I pursued my sport. The sport didn’t work out any-- not quite as well as I’d wanted it to. The education worked out a bit better than I expected it to [laughs] and I found myself as a teacher and I taught for a while and I loved teaching, I really like the idea of teaching but the bureaucracy gave me the shits. I couldn’t deal very well with the Education Department and so I got frustrated with that, and then a position came up in the Education Department as a sports administrator and that suited me down to the ground because that was my second love.

So, I combined the two. I worked in the education system but organising their sport on a statewide basis. You know, organising state teams, organising competitions, organising all that kind of stuff. That was my job and then that led to other opportunities in sports administration generally. Became a general manager of one of the league football clubs in Adelaide and then Adelaide City Soccer Club. I was general manager of that as well, so that led into that career.

"I got talked into undertaking university education at the same time, and that was fortunate because it’s the education rather than the sport that’s paid most dividends for me"

Finally you entered body corporate management. What drew you to it and how did you find yourself there?

By accident, completely and utterly by accident. I was working in a school, not in a teaching role but in an administrative role and I literally jumped the fence with a lady one night after a school event. The gate was locked, we couldn’t get to our cars so we jumped the fence and she just-- she was a complete stranger and she said that her husband and her had just gone into a fairly newish sort of business that was in a growth industry they thought. Now this was in the late nineteen eighties and body corporate management-- strata management was a relatively new concept. The industry had only-- had only been in existence ten to fifteen years, so it was something absolutely brand new to everybody and nobody knew anything about it.

So I got in at the ground floor, she literally-- jumping that fence, created a relationship and they wanted someone else in their new business to help them and I was it. So, I-- it was just a by chance thing that I happened to land myself in this industry and I’ve been in it now for thirty years.

You had top positions in various companies and you could have stayed in those roles. Why take the risk of starting your own company, Community Living?

Yeah, good question. Because-- that didn’t happen by accident. It did happen as a consequence of actions. I worked for two large companies, one in Adelaide, one in Melbourne and the-- my future-- I had to make a decision about my future because the company that I was working for weren’t overjoyed with me, I think they were overjoyed with my performance but I had a falling out with the guy who owned the business and so I was at a crossroads and I literally had to find another job, and I did and it-- I was going to go into partnership with a friend of mine in Queensland in a body corporate management business. The deal was virtually done and at the time the contract was to be signed, the bloke who was selling the business to us reneged, and so I was left high and dry with no business to go to.

So I did work for my friend: the bloke I was going to go into partnership with. He already had his own business. I worked with him for a year and then an opportunity came up in Melbourne which I’d created earlier which was for the management of the first real community title in Victoria. It was going to be a large scheme of-- ended up being eight hundred and fifty lots. So by anyone’s scale it was going to be a significant development and it was going to be a landmark development because it was going to be the first in the state.

So, it was innovative and all of that appealed to me. The Macquarie Bank was developing this huge site and they were impressed with my background. They were impressed with the knowledge I could bring to the table because I’d been on a study tour in the United States and I had actually observed the way that they built communities, proper communities, out of people, not just buildings and Macquarie Bank was interested in my ideas on that and that was the start of it. They said, "Well, we’re going to appoint you as the first manager”. So I worked with them with the development of the scheme and managed it for six years there after it was completed. It was completed more or less after a number of years but after six years it had been complete, I had been managing it all of that time.

So that-- so to do that I said, "Okay, I’ll establish my own company and we’ll start it from scratch.” So it was a start-up with a brand new concept which demanded innovation. There were no precedents. Yes there was the law, we knew-- I knew the law but no one had put together a community like this was going to be in Victoria. So we had to glean stuff that they were doing elsewhere, predominantly in America, and we had to fit that into the local requirements and so we had to think it through and build something from scratch, and I really liked that. It’s a challenge that I really relished.

"Proper communities, out of people."

Community Living was a different approach.What were the challenges of such a radical approach and how did you overcome them?

Well, I thought if ever I went into business by myself-- because I’d worked for two large companies at the top, very top level as general manager and I thought, "If ever I was going to do this by myself, I could make up all the rules. I could make up all the objectives. I could determine how we were going to deliver services”. I thought, "I’m going to do it radically differently from-- from all the conventional ways that the firms that were engaged in the industry were doing.

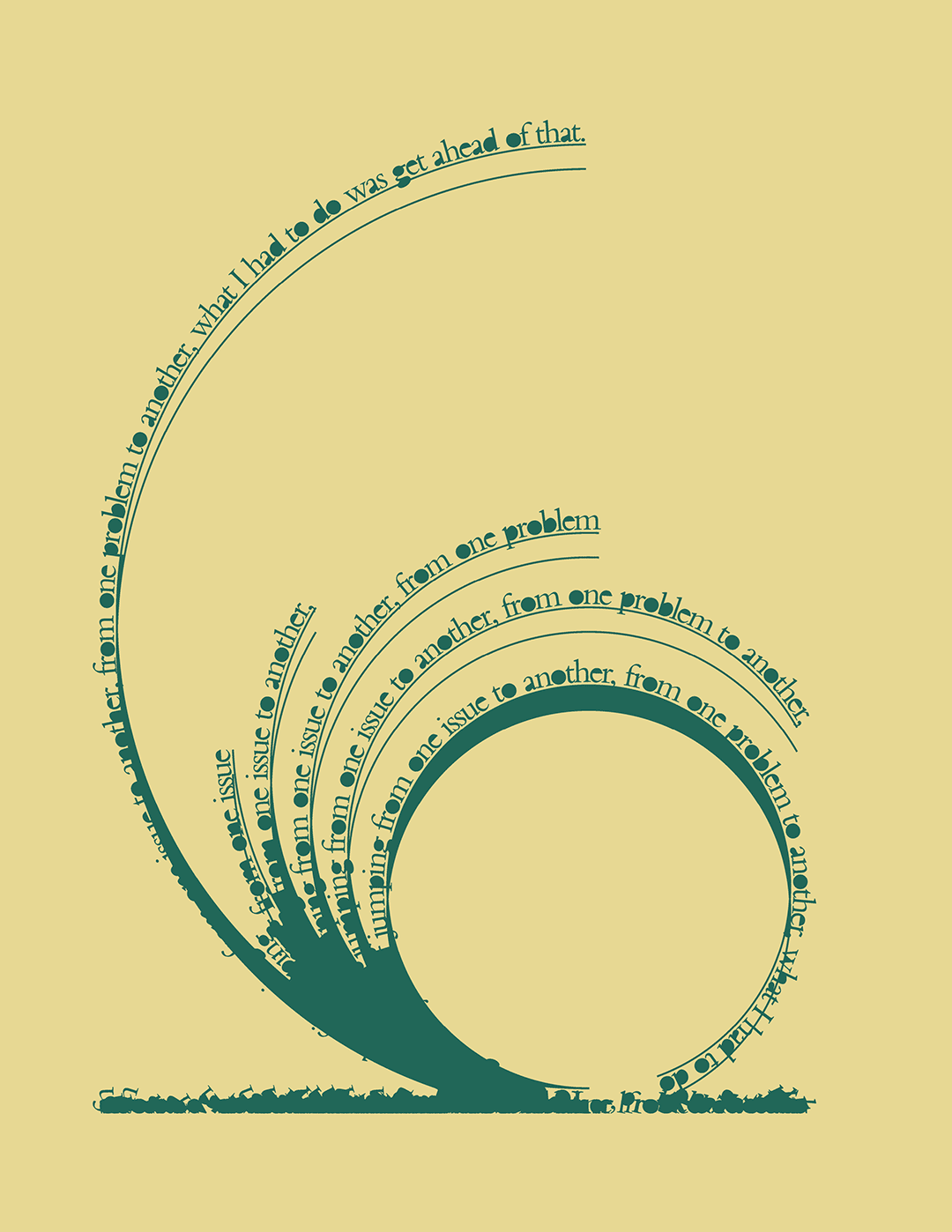

So, there were a couple of principles. I thought, "Well, the first thing I want to do is to cut out telephone calls because that drives strata managers crazy”. The phone rings all the time, you’re jumping from one problem to another and I thought, "You’ve got to break that cycle.” So, I was determined to do that, I-- I thought-- I came up with a really innovative way [laughs] at the time of having an office that never closed. So, I was contactable by the clients twenty-four seven and that was unheard of in the industry. And I thought, "How am I going to do those two things” and obviously I had to rely very heavily on technologies - on alternative ways to deliver services and to communicate with the clients and it just so happened that that was right at the time when computers were invented. [laughs] No, they were invented but they became available for public use; Joe Blows could go into a shop and buy a computer and in the days before that, they weren’t on the shelves. Computers weren’t on the shelves, they were you know, big IBM mainframes but when the home computer became available then it opened up things and I grabbed this home computer and I started to rev it up and do all the sorts of things it could do. I stretched its imagination to do the-- an applied it to the business logistics and that worked tremendously well.

So, I contacted everyone electronically. I switched them. I switched them off the phone and into electronic communication - mostly email - but I didn’t just sit there and wait for people to email me. I thought, “Well, to change that cycle of jumping from one issue to another, from one problem to another” - what I had to do was get ahead of that. I had to think of a way of fixing things before they got broken, you know? Like, the client-- if something would break, a client would ring, then the manager would react. That’s been the formula for every company that’s ever been in this industry. That’s the conventional wisdom: sit there, wait for the phone to ring, people will tell you there’s a problem, go and fix it then move on to the next problem because the phone will ring again. And I thought, "Cut the phone connect and address the issue about how do you stop things breaking down?” Well, I figured you do it in two ways: first you visit properties. You’d actually go and look at the properties and find the problems yourself, not wait for the client to find them. And the second thing: the second part of that was to work very, very closely with management committees that were elected within the strata corporations.

So, if you work closely, really closely with the people and you help them, one to one as a continuing exercise, then I figured, when they had a problem, you’d be aware of it immediately, you’d deal with it immediately right there and then so it didn’t cause a problem for anybody. So, being forewarned, by being aware of what needed to be done, being close to the people at the-- in the administrative-- carrying administrative responsibilities that meant that you could be as aware as anyone could possibly be of the needs of that client and so you could deal with that before the phone calls, before the clients realised there was an issue and that worked really well. Mind you-- mind you not every company could apply that approach to all of their clients. Because I was a startup and it was an innovative time I also made another rule, I said, “keep your office open around the clock and make a close connection with the clients, cut off the phones.”

The other thing that I did was decide that I’d only look after large groups. I wouldn’t look after small ones, which meant that with the bigger ones, you could get closer to them, you could work with them, you could fix their problems before they became problems, then, you know, it would work because you didn’t have-- you weren’t overwhelmed with, say a hundred or hundred and fifty clients. You might have been dealing with thirty or forty clients. So, that helped a great deal, the way I structured the business actually helped me to deliver services very efficiently, which fundamentally meant that we were dealing with day-to-day closely with clients and delivering benefits to them before you-- before you needed to be reactive, before things problems which got reported, which then you had to run from one fire to another to you know put it out.

"To change that cycle of jumping from one issue to another, from one problem to another - what I had to do was get ahead of that."

The theme is that you’ve certainly done things a little bit differently along the way but ultimately why take such a risky and sideways approach to business?

Yeah, it-- I’ve got to say you’re right, it is risky, it’s bloody risky but I’m a really conservative fella. Like, for example, I never gamble. When Melbourne Cup comes around, they say, “Which horse do you want?” and I say, you know, "Oh, take a pick, I’m not really interested.” I’m not a gambler in terms of wagering money but when I look back on it, I’ve never been afraid of putting all my chips on the table and saying, “I think I’m right, and I want to have a go.”

So, in a funny sort of ironic way, I’ve not been risky with money but I’ve been risky with my whole life. Like, you know, I’ve just put everything out there and said, "I think I’m right, I think it’ll work” and fortunately, most of the time it has.

"I had to re-engineer my thoughts."

After establishing Community Living on your own, you were offered a position back in Adelaide after living in Melbourne for many years. Why accept the reverse challenge of going back into managing another company? And how have you found it?

Yeah, it’s a reverse challenge, you’re dead right about that. I sold my business. Someone actually wanted to buy it! One of the big players. There are two big players in this country in terms of body corporate management operations and one of those two pursued the purchase of my business over about a nine month period and I thought the timing was right for it for a number of reasons.

I thought, "Yes. I’ve been innovative, I’ve achieved a lot. Someone wants to pay me money for that” so I said, "Yes, I think we can do a deal but I’m not ready to retire. I’m not ready to take the money and run. I want to keep working.” So, the arrangement with them was that I would continue to work with them, even though they’d purchased my business and in fact they let me work in the business and on the business. So they really took over the ownership but they left everything else the way it was. Yes, we were integrated into their big pool of acquisitions but-- so we had a lot of cousins that we were dealing with but fundamentally they just let me keep running the Community Living part of the operation for a year basically and then they said, "We’ve just acquired another business in Adelaide and we want you to manage that” and it was an opportunity that I took because Adelaide’s the home town and my wife and I have family here so we-- we accepted that offer and I came back to Adelaide.

Now, it was-- there were twelve employees in the operation, so it was middle sized - not small and it’s not big. It’s a middle sized operation in terms of body corporate management but it was a reverse challenge because it was a business that operated nothing like Community Living. So, all of the innovative logistics that I’d set up with Community Living didn’t apply to this one, so really I had to re-engineer my thoughts because here was a commercial concern that was profitable, working well, it was quite efficient and so in a commercial sense we didn’t want to upset that but I’ve got this feeling that-- that clients’ needs change, they evolve over time and I thought, "Yes, this is a successful operation now, it’s been a successful operation for some twenty three years” but I thought, "In the next twenty three years, what’s it going to look like?” And I thought, "No, I can’t see that it’s sustainable into the future.”

I think clients will want something different and they’ll want the service delivery changed because it was a very- - it’s been a very reactive firm. That is, sit by the phone, wait for it to ring, then attend to what people want and run around with a fire-truck putting out fires and if -- if you do that --- if you do that enough, - if you pour enough energy into that you’ll keep your head above water. That is, you’ll keep the clients so you’ll maintain profitability but I-- I think that just burns everyone out, that approach. You can’t keep doing that all of the time. Managers get burnt out, clients get frustrated. It’s a matter of sort of managing people by satisfying their minimal expectations whereas the way that I’d prefer to do business is to extend their expectations, extend clients’ expectations all the time. You know, give them a service that they take for granted after a while but they’re impressed with. Like-- that doesn’t leave anything in the tank, so they’re totally satisfied and I think if you totally satisfy your clients, mostly then, you’ll keep them. Not every time. There are odd things that happen and you lose appointments for all the wrong reasons but, what else can you do? I think you've just got to say, “Well, let’s really “kill” these people with providing every service they could possibly want so they don’t have any issues.”

And so, it meant in accepting the appointment in Adelaide, I had to change the psychology, I had to change the way that the company looked at the services it was providing and the way it was providing it so that-- yeah that was a real challenge, that’s a real big challenge to do that. An enjoyable one because I sort of figured I had answers to those challenges. I knew what I wanted to do to meet those challenges but none the less. Yep, they were hurdles that had to be overcome.

"I’d prefer to do business is to extend their expectations, extend clients’ expectations all the time."

You don’t seem like slowing down even after such a long career? What’s next?

Yeah, well, I don’t know what’s next really and I’ve got this understanding that none of us can anticipate exactly what the next opportunity is going to be. For me, fortunately, opportunities have always arisen. There’s always been something, even at times-- at various times-- when I sold my business I thought I was going to cruise, I thought, "Well, yeah, I’ll keep working for a few years until I run out of petrol” and you know there have been occasions in my life when I’ve literally thought, "Well, what more can I do?” You know, now’s time for coasting-- now’s time to just do the sorts of things that I like to do but it’s never been that way.

There’s always been something that’s come up, another opportunity that came up out of the blue and you think, "Wow, alright, I’m going to grab that and then I’m going to apply my wits and my knowledge and my experience to it and I’m going to-- I’m going to create something new” and I don’t know what the next one will be absolutely. It’ll probably-- it’ll probably involve using the skills that I’ve got that I’ve developed in the industry but it means that I’ll continually be on the outlook to improve technology-- apply technologies. I don’t think that we do that enough. The technologies are there but it seems to me a lot of businesses don’t understand the technologies or ignore them because they could make much better use of them to make their work more efficient, - that is, to achieve more for the client and for it to actually cost less and to take a little bit less time.

And I think you can do that if you apply your mind to it and understand what you need to do a job and then look for the technologies that can deliver that and I think people look at it in reverse. I think people look at the technologies and they say, "Wow! How can we use that?” and I suppose that works for some people but for me I’d rather work the other way. “What application do I need? What do I need to achieve? Now how are we going to be able to do that?” And then just find the tool -- find the right tool in the toolkit to say, "Ah, this is the one that helps me do that job.” So, yeah, I’m forever looking for that. Forever looking for a new application that helps me do my job better.

I’m always looking at ways, psychologically, to understand what the client needs. The client is not always aware of it, although you try to ascertain that, you try to get from the client as much as you can about what their needs are but you interpret that and you say, "Yes! I think I understand and I think I can visualise what needs you will have going forward” and so, dealing with those. Rather than coming back to it-- rather than that reactive thing about, "Okay, I’ll sit here and wait for you to tell me what you want me to do and then I’ll do it.” I don’t like that idea. I like to be proactive rather than reactive.

So, whatever opportunity comes up that provides me an opportunity to do that - to say, "I can improve the lives of my clients - just by millimetres, not by a hell of a lot.” I wish I could but in the industry that I’m in, helping people a little bit and by a little bit is a noble expectation. Not going to be able to save their lives. Not going to be able to change their lives but to be able to improve what they are doing in some small way and focusing on that, focusing on how we can create a better way of delivering the services to those people, that’s what it’s all about. So I’ll keep hunting and the opportunities will fall out of the sky as they always have.

As much as we try and ferret them out, actually, it happens almost by chance and when the next one pops up, I’m ready to go for it.

"The technologies are there but it seems to me a lot of businesses don’t understand the technologies or ignore them because they could make much better use of them to make their work more efficient."

Find Bryan on LinkedIn

Proofreading by Cinzia Forby. Photography by Lorenzo Princi.